A year ago as the EU ETS price showed clear signs of a second step change downwards (in 2008/9 from €25 to €15 then in 2011 from €15 to €7), the EU Commission was resolute in its view that the mechanism was working, that it was responding to changes in the market and that all was well in the house of emissions trading. Rightly or wrongly, that view was backed by most of the major industry and business groups as well, to the extent that even if the Commission had thought that action was necessary it had absolutely no mandate for action.

But a year is a very long time in business and politics and this week, with the backing and support of many business groups, the EU Commission released its first concrete thinking on the state of the emissions market and began the political process necessary to attempt to address the problems.

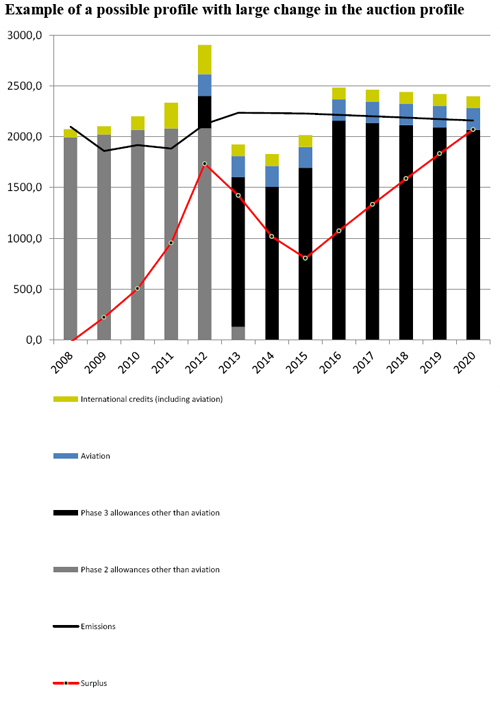

The initial report (with the somewhat long title “Information provided on the functioning of the EU Emissions Trading System, the volumes of greenhouse gas emission allowances auctioned and freely allocated and the impact on the surplus of allowances in the period up to 2020”) spells out in pretty stark terms the scale of the allowance surplus that now weighs down the price. It also highlights the fact that it won’t be until well into the 2020s that this shows any real sign of going away through the natural development of the system and its declining cap. The report then lays out a course of action, with three proposed levels of severity examined.

That course of action involves skewing the allowance distribution in Phase III, such that less allowances are auctioned in the early years (2013 to 2016) and more are auctioned in the later years (2017-2020) – but the total number of allowances to be released remains unchanged, which means that there is no overall change in the surplus position that is forecast for 2020. The proposal is called “backloading”. The Commission has limited power in this area and even this step has required them to propose a very minor change in the Emissions Trading Directive to clarify the role that they have in the carbon market.

The largest backloading proposed is (quoting the Commission working paper):

“a reduction by 1.2 billion in the first three years of phase 3. This would result in a large reduction in the surplus in 2013. Nevertheless the reduction in the surplus remains significantly below the increase experienced in 2011 and expected over 2012. By 2015 the surplus would be below 1 billion unused allowances compared to a case where no changes in the auction time profile were implemented. After 2015 the auctioned amounts would actually increase significantly, resulting in an issuance of allowances well above future emission levels. This would drive a re-emergence of the surplus. Total annual issuance in the period 2016 to 2019 would be higher than in any year in phase 2 bar 2012. The decrease in auctioned volumes early in phase 3 would require drawing on the existing surpluses to make available the necessary allowances to the market to comply with emissions. This type of change of the auction time profile is thus likely to give strong temporary support to prices in 2013 to 2015, but would put downward pressure on prices in the second half of phase 3.”

At best, the move buys time and gives the Commission some breathing room to gain agreement on the necessary Phase IV parameters (rate of cap decline, possible use of auction reserve pricing, sectoral coverage, free allocation levels etc.), but doesn’t inflame the whole ETS target debate by proposing a full set aside and cancellation of allowances. This latter step is what is really needed, but may be politically too big a bite to chew on given the recent animosity over the Low Carbon Roadmap to 2030 and beyond. As such the Commission has opted for something that it thinks can be done today, rather than fighting the bigger fight over targets which it will have to do anyway in the context of Phase IV. Better leave it for that discussion!!

It is important to reflect on the role of the business community in all this. None of this would have happened were it not for a shift in position from opposition to market intervention to support. This isn’t to say that all business groups support such a move, but today many do. The catalyst for support was the gradual realisation that if the ETS failed to trigger a change in the (power sector) investment profile going forward, governments would inevitably make the decisions for business by applying mandates.

Some business groups remain opposed to intervention, but these now appear to be the ones that have always opposed action to reduce CO2 emissions. While they claim to support the ETS, they strongly argue the case that the market should be left to its own devices. The real agenda is often very different. With the high levels of free allocation that have existed during Phases I and II, the businesses involved are more than happy with the status quo which requires little more than administrative compliance (it certainly doesn’t require emissions reduction through projects and investment).

The battle isn’t over yet and much remains to be done, but this week saw an important step forward and one that hopefully leads to the restoration of the ETS as the primary driver for emission reduction investments across Europe.

I hope you realise the IPCC pseudo-science is based on 5 basic physics’ mistakes and because CO2 enters IR self-absorption by ~200 ppmV, there can be NO CO2-AGW [the mechanism involves switching off IR emission in those bands at the surface].

I suspect that the global study of physics has got well past the point of making “mistakes” such as you describe.

It is clear the Europe becomes economically uncompetitive. Because of high taxes and labour cost the industry is leaving EU. ETS is just another tax. This looks to me like economic euthanasia. The only business plan which works in EU is to rely on subsidies and protective regulations. There are still technological centres in EU but I don’t believe that these centres can survive long term without link to the industry and under high tax regime. I hope that EU ends on Japanese road of economic stagnation rather then in decline and with social unrests looming over southern Europe.

Physics depends on experiments with observations being the highest arbiter in validating hypothesis. Runaway AGW theory based on positive water vapour feedback augmenting CO2 forcing has significant shortfalls. While qualitative CO2 effect on atmospheric temperature is well documented I would say that climate models trying to model complex atmospheric behaviour are unsuccessful so far. The reason is that they are not supported by observations. Actually, it is quite difficult to observe global climate. If we can’t observe it how can we model it?

The major failure of climate science is in insufficient quality of climate observations while pretending that unrealistic models can make-up for lack of observations. While some satellite observations are quite reliable (troposphere temperature) the other are clearly insufficient. E.g Earth energy budget with missing heat and non existing troposphere hot spots. The hard truth is that the key climate indicator Ocean heat content can be measured with some accuracy and in “shallow” ocean only for last 7 years. Previous and/or deeper data are largely spurious and insufficient. Land based thermometer series are in disarray plagued with pathetic quality, lost or hidden data and large spurious signals. Sea level measurement is in big schism as tidal gauges don’t agree with satellite altimeters which have insufficient accuracy to measure subtle changes of highly unstable surface layer from the distance of hundreds of kilometres. Paleoclimatology suffers from cherry picking and ideological infighting around “hockey stick”. IPCC doesn’t make it better with its ideological approach, politic agenda and tribal behaviour.

The only way out is through long and hard normal way of scientific work. The less politic agenda and less lobbying will be involved the faster climate science would join ranks or standard science. David’s blog only show pathetic state of climate science being tortured to give required result.

Saying that we are facing apocalyptic AGW caused by increased CO2 concentration is simply political agenda. Saying that small tweaks to CO2 emissions can change anything is just exaggeration. I’m not saying that we should no nothing. I would advice first of all investigate the issue using standard apolitical and non ideological science. Then I would advise to continue building technologically based free and prosperous society which addresses the “low hanging fruits” problems first. E.g pollution in the developed world was solved by exporting it to the 3rd world only. CO2 emissions pose no problem today and it is quite likely that it will be non-problem also in the future. All we need to do is to ensure that our successors have enough resources to solve the coming crisis. But, we should first solve our own crisis. And I don’t think that this can be done by any CO2 tax.

Jiri,

This particular posting isn’t about climate science at all, but about recalibrating a market instrument that has got out of alignment. Perhaps you should try to comment on the content rather than persist with your negative view of mainstream science. I know that you read my posts and I welcome your input, but you should also know that I am not one who tends towards alarmism or runaway warming.

David

My previous comment was not on the main article but on your previous comment saying that physics got past making any fundamental mistakes. Sorry for off topic. Regarding ETS my opinion is clear. ETS is reaction to the non existing threat and it is inflicting damage to the economy. Because the economy is struggling ETS is causing less damage. You are lobbying to reset ETS so its negative effect is reinstated. My advice would be to remove ETS altogether to help economy to recover. There is no justification for ETS even from runaway AGW theory point of view. Using alternative theories ETS is just pure nonsense. Why EU is still pursuing ETS? Why elites are tolerating tribalism of IPCC suppressing common sense and alternative views? IPCC is political body – not scientific and AGW dogma is just a tool for elites to promote some agenda. We are back to medieval times but instead of religious dogma we have EU elites, entrepreneurs and political activists promoting AGW. Why US senate allows intense discussion (e.g. this week hearing) while the debate in EU is dead? Climate science is probably the only field where this is happening and EU is the worst place. Last few decades could be considered dark ages in climate science. Fortunately, there is growing internet community of scientists and interested public which can share information online. So far elites don’t have much control over it. Sooner or later ETS is destined to fail. I hope we can help to end this madness ASAP to limit damage caused.